School Is for Learning to Read

Many students are falling behind in reading, and reading experts are responding by questioning the way reading is taught in schools, especially to early readers. Are students learning what they need to in order to be literate readers?

How Reading and Learning Are Connected

Fourth grade is considered a major turning point because reading goes from being largely accompanied by pictures to not having many or including diagrams that also require reading. Students go from “learning to read” to “reading to learn,” and if they haven’t gained mastery of reading by now, they experience difficulty learning everything else. Yet the literacy rates among fourth graders nationwide have been hovering around 60% since the mid-1990s. That means that 40% of fourth graders are behind in reading, and those early fourth graders are now almost 40 themselves.

The Matthew Effect, named by reading expert Keith Stanovich, describes conditions in which how a student performs in early reading snowballs in later grades. In other words, when a student adapts quickly to reading, they will read better by graduation, while students who struggle will disengage further as reading becomes more complex. Surveys show comparable rates of graduating students who were behind in reading to the fourth graders, with around 40% of high school graduates still struggling by graduation going back to 1992.

The Science of Reading

There are 15,000 syllables and 44 sound-letter combinations in English, and while people learn these sounds as children through verbal interactions with the people around them, learning to match the sounds to letters is an acquired skill. This process is called decoding because language, according to experts, is a code that is based on the structure of words and sentences. Readers who can decode quickly understand more of what they are reading and expand their vocabulary to include more words faster as a result.

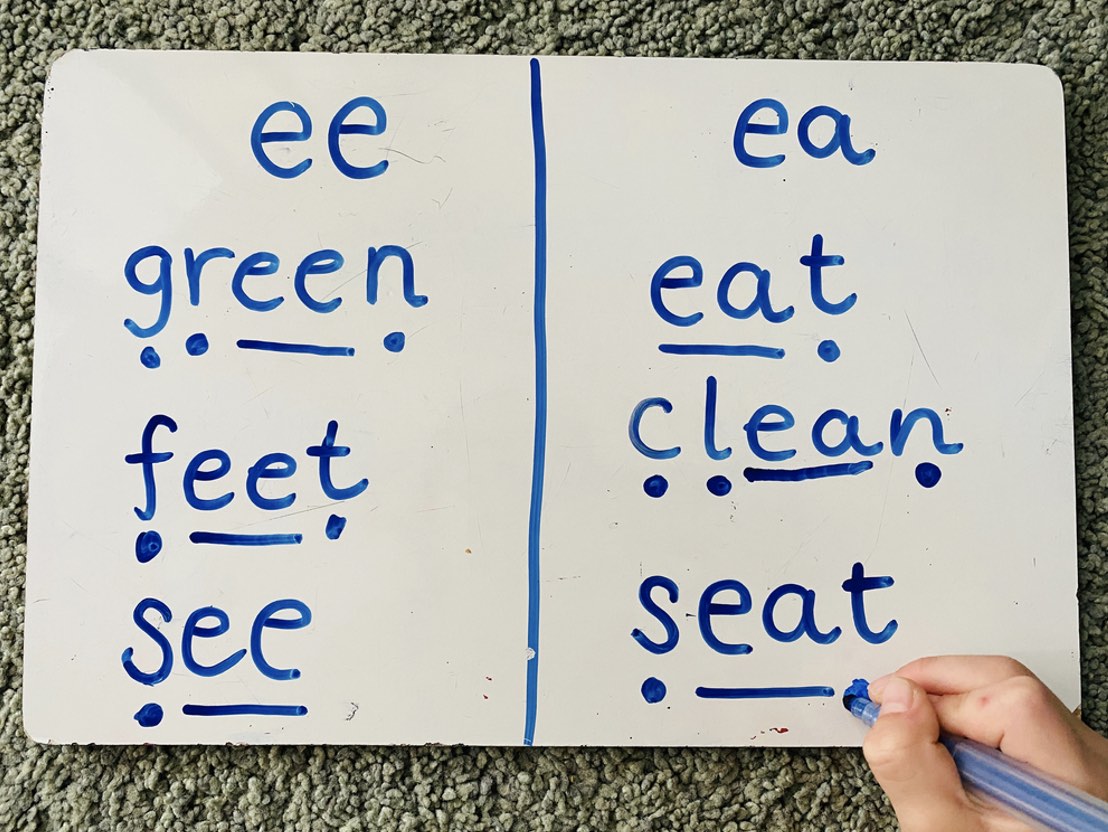

When a child sees a word, the first parts of their brains to become activated are those associated with vision and speech. These studies indicate that a large part of learning how to effectively decode when reading is based on phonemic awareness, which is the ability to recognize and use all those sounds and syllables to form words, and phonics, which is the learned association of sounds with the symbols – letters – they are associated with in print.

Readers who can master these two skills build three more that are the final components to literacy. Readers who can decode quickly build fluency, or the ability to read faster. The more exposure students have to reading, the more they build vocabulary, the number of words they know. All these elements create comprehension, which is the ability to extract meaning from text.

What’s Wrong with How Reading Is Taught?

Many schools claim to teach “balanced literacy,” which includes some bad habits usually formed by kids who struggle with reading. Despite phonics being shown as the most effective method of introducing readers to words, many educators and administrators fall back on methods that may actually impede the teaching of reading. One reason for this is because there is no specific “balanced literacy” curriculum, which makes almost any method fall under its umbrella.

Balanced literacy is often given borrowed legitimacy by what is known as the “whole language approach.” This method teaches students to recognize words on sight rather than sounding them out. The whole language approach is sometimes useful because many words in the English language either have no phonetic pronunciations (such as if, the, or one), or are exceptions to phonetic rules (such as jazz rhyming with has). The whole word approach is a great supplement to phonics instruction, but is not in itself an effective way to teach reading.

The whole word approach is often amplified by applying it in other ways, such as cueing words. This refers to a method of “reading” words by examining their position in a sentence, whether the reader has experienced them, or whether they are proper nouns. What results is readers “guessing” words rather than connecting them to speech.

Why Balanced Literacy Doesn’t Work

The teaching of students with dyslexia puts a spotlight on the problem with balanced literacy because phonemic awareness and phonics are the best ways to teach them to read. Phonics is a useful skill for all students, but especially for those who struggle with reading. When students can match words they read to what they hear, they learn them faster and more effectively. Balanced literacy does not adequately teach phonics, sometimes omitting it entirely from the reading curriculum.

Parents who can afford to either use tutors or put time into working with their children on reading, but not everyone can do this. Further, schools in low-income areas that have implemented science-based reading instruction have seen steep improvements in literacy, indicating that tutors and home schooling are not necessary when these methods are used in the classroom.

As the pandemic forced lockdowns during 2020, a lot of parents witnessed firsthand how their children were being taught to read, and how much frustration they were experiencing with the process. This has prompted a lot of parents to re-evaluate how their children are being taught and speak out for improvement.

What Can We Do?

The most important support we can provide students who struggle with reading is to help build their phonemic awareness at home, especially if they are not getting the instruction in school. Learning to read doesn’t need to involve sitting down with books. There are opportunities all over the house to reinforce phonemic awareness and phonics, as well as while out and about.

Some ways parents can help struggling students practice reading at home include:

- Use apps like Readability Tutor which helps children practice and develop improved reading skills in all areas

- Practice sounds with them by teaching them the names of things around the house and spelling the words with them. Enunciate syllables when you say words, sounding it out for them. When you model this technique, they begin to learn it.

- Read to kids, even if you can’t sit and read books. Everywhere we go there are things to read, from parts of the cereal box at the breakfast table to the signs at the park and on the street.

- Encouraging kids to use their imagination when learning makes it more fun for them. As they recognize the letters, challenge them to find objects that begin with certain letters or sounds, or to use specific-sounding words to describe things around them.

- Sing songs and make rhymes. Poetry works because we pick up on rhymes very quickly, and this can be used to familiarize kids with the way words sound, making it easier for them to associate the sound with letters.

- Let kids have experiences so they can match words to them. The more they are exposed to, the more they build vocabulary, which they can then associate with the written word when they’ve used the word themselves.

- Ask how your school teaches reading. Teachers should be able to explain their methods and the curriculum, and this can help give you an idea of how effective they will be at teaching your children to read. Watch out for terms that are “balanced literacy” or “phonics-based,” as these can be indicators of the classroom’s instruction.

Reading Is for Learning

Reading is something people use their entire lives, and students who struggle with it early often struggle through school and beyond. Everything students learn in school involves reading and learning new words, which is why it is important for students to keep up. A child’s entire education is learning to read, so it is vital that schools teach literacy effectively in order to succeed at their goal.

Advertising disclosure: We may receive compensation for some of the links in our stories. Thank you for supporting LA Weekly and our advertisers.

The post School Is for Learning to Read appeared first on LA Weekly.